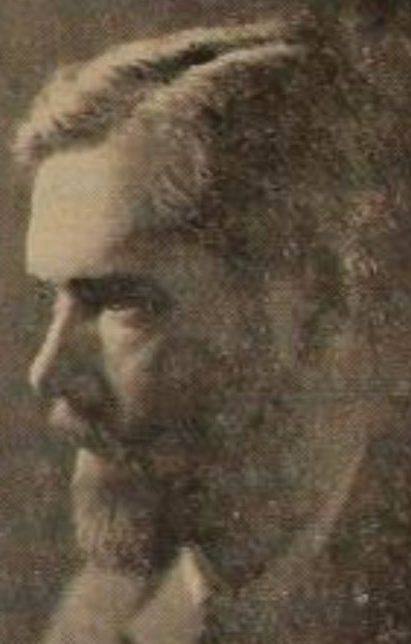

John MacMurray was born at Maxwell, Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland, in 1891. During the First World War, he enlisted as a private and in 1916 was awarded the Military Cross. After the war, he returned to Oxford to study history and philosophy. After graduating in 1919, he taught philosophy at a number of universities across Europe, including at the University of Manchester, the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, Balliol College, Oxford, and the University of London, where he was appointed Grote Professor of the Philosophy of the Mind and Logic in 1928. In 1930, he was invited to give a series of lectures on “Reality and Freedom” for the BBC, which brought him public recognition and led to the publication of Freedom in the Modern World (1932). At the University of Edinburgh from 1944, MacMurray authored several books and specialized in the philosophy of freedom and the interpretation of religion in the modern world, including Interpreting the Universe, Reason and Emotion, and The Boundaries of Science. He viewed people in terms of their relationality and agency, rather than in terms of individualism and cognition. He retired from teaching in 1958. After retirement, he and his wife became members of the Society of Friends. He died in 1976. A John Macmurray Society was formed in Canada in 1971 and was later replaced by the International John Macmurray Association, and the UK-based John Macmurray Fellowship was established in 1993 to encourage interest in his life and engagement with his work.

MacMurray held three lectures on the conditions of freedom: The Relativity of Freedom, Contemporary Conflict & Freedom in Fellowship. He arrived at Queen’s on January 11, and remained for the month, during which he also spoke with a large number of student groups. All classes were canceled so that students could attend the first lecture. He put forward an understanding of freedom as the ability to do as we please; thus, the removal of obstacles to this ability is equivalent to increasing freedom. His lectures developed Rousseau’s paradox of freedom, suggesting that while we are born free, in practice freedom must still be achieved by fulfilling a set of conditions. Firstly, we must accept responsibility for our actions and their consequences. This means that freedom involves a relation between what we intend and the power we have to carry out our intention. He also considered the social aspect with which we must engage ourselves to achieve freedom; human nature is inherently social, so our resources and intentions are also social and to achieve them we must co-operate and gain the permission of others. To believe in freedom is to also set others free. Here, he disagreed with the assumption that technology was the means by which human freedom was being enlarged, instead he argued that freedom is reciprocal and dependent. He outlined two methods for propogating co-operation: the moralization of human desire (religion) and the control of the means of realizing these desires (politics). In our time, effective justice is key to achieving freedom for all, to uphold a unity of values designed for the betterment and freedom of all. Moving forward, MacMurray believed, a universal unity of fellowship (not a world state, per se) should be established to ensure the freedom and justice of all peoples.

In his second lecture, he discussed the issue of economic interdependence of the world system while political organization still relied on independent nation-states. Since the world system did not have a shared instrument of justice, each state needed to attempt to control the world economy to the benefit of its citizens. “A system of independent states in a world that is economically one society cannot achieve justice and must destroy freedom.” While the League of Nations demonstrated that freedom could only be defended if it were worldwide, MacMurray suggest that there was no current effective world government that recognized that freedom is not an exclusive Western possession.

To achieve world freedom, MacMurray’s third lecture argued, external unity brought by law is not enough – it must be joined by an underlying spiritual unity achieved through religion. Over time, the connection through shared blood has been replaced by an emphasis on citizenship and birth. Inner unity and community must be extended beyond the borders of the nation-state, to encompass the world as a whole with common values and a common way of life. This is not to suggest a world government is needed, rather, we must think of world unity as fellowship. This is the religious task of our time, and its success will determine the future state of freedom. Democracy itself, is not a guarantee of freedom, freedom has deeper roots. Democratic institutions may be necessary for political freedom, but that is not the whole story. The modern world may maintain freedom as a goal, but actually seeks only to increase power through capitalism (wealth used to gain more wealth); political power (power used to increase power); and science (as mastery of the techniques of control).”

Listen to an excerpt or read the full transcript of MacMurray’s lectures below.

Download the MacMurray Lecture - Part 1